Some Rando Viking

Cards on the table, I have no idea who this Thorgal fellow is. Child of the stars? Some rando Viking? In need of a shave? Apparently he’s the main character of a Franco-Belgian comic book. Until I played Joanna Kijanka, Jan Maurycy Święcicki, and Rafał Szyma’s board game, I wasn’t even aware that there were Franco-Belgian comic books.

But that’s the impressive thing about Thorgal: The Board Game. Its alt-history world is so vibrant, its rough-handed characters so vividly drawn, its gameplay conundrums so compelling, that it hardly requires any introduction at all.

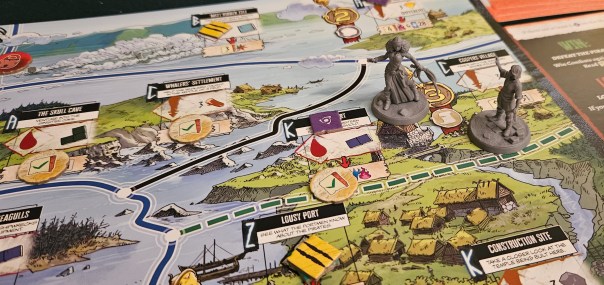

From what I can tell, Thorgal occupies a world not unlike our own. The cultures we know — mist-swept Danish settlements, steaming Mesoamerican jungles, sandy caliphates — are present and accounted for. The difference is that everybody’s mythology is, well, not so mythological. Giants lumber across the horizon, dwarves dip between realms, and magic is very much a tangible thing that sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t according to rules that always remain just out of reach.

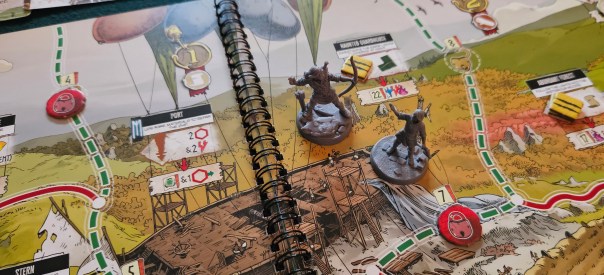

Yet Kijanka, Święcicki, and Szyma imbue each scenario with a smoky earthiness that prevents the game from floating away on fantasy airs. Multiple chapters present its characters with fantastical problems, such as launching a prison break on a giant’s farm or escaping an otherworldly maze. But these problems are always grounded in real-enough considerations. That aforementioned prison break, for instance, sees your characters scraping a beehive for honey and dodging bear-proportioned mice as they try to creep into the giant’s shack. More often, its problems are all too familiar: slavers who have captured your family members, a pregnant woman escaping her abusive father, some petty tyrant terrorizing his scrap of rock. This is a world where you might be trampled by a giant or executed on the whims of a spoiled lordling. Whether it comes at the hands of some mythological creature or a punk holding two feet of sharpened metal, death is death.

Okay, so what are we actually doing here? For the most part, trying to survive. Each chapter — there are seven in the base game, and no, they aren’t particularly replayable — sees some combination of Thorgal, his wife, his would-be lover, and his son washing up on the shores of another perilous adventure. More than window dressing, each of the game’s chapters is full of novel touches. Some simulate stealth, others see you smuggling cargo, and others still require some measure of puzzle-solving.

In each case, there’s a very real chance of dying horribly. Like the setting itself, the gameplay is largely grounded in mundane necessity: gathering resources, getting your bearings, starting to push back against whoever or whatever is threatening your life today. It’s scrappy and raw, and often comes down to razor-thin margins between success and failure.

The system underpinning these actions is functional enough to require careful consideration even if it doesn’t make much sense within the logic of the game universe. The gist is that you have a row of action cards, things like fighting, gathering resources, picking up items, moving around the map, and so forth. Each turn allows your crew to alternate placing four discs on these cards to trigger their corresponding effects.

This year alone, we’ve seen at least three other prominent titles include action systems that function “outside the fiction,” so to speak. Whether it’s the dice assignments of Eric Lang and Calvin Wong Tze Loon’s Mass Effect: The Board Game: Priority: Hagalaz, the carefully parceled cards of Kevin Wilson’s Escape from New York, or the card-parceling and action-line system of Corey Konieczka’s The Mandalorian: Adventures, there’s a recent trend of overtly separating the actions your characters carry out on the board from the method that you, as the game’s player, use to assign those actions.

But two details elevate this action system into the strongest of the four. The first is that the relative position of your discs often adjusts the efficacy of each action. Some actions trigger a bonus if there’s only one disc located there; others become more powerful for every disc placed on that card, or even for every disc situated to its left. This encourages an uncommon thoughtfulness about each action. It isn’t enough to select the best action for your own turn. You also need to consider the needs of your companions. Shifting discs that allow your fellow players to make the most of their turns breeds a certain camaraderie. The opposite, taking selfish or short-sighted actions, starts to make your characters feel like people who’ve just endured an over-long family vacation.

What’s more, the action-line is never static. Every scenario presents its own six cards, themselves little nods to that chapter’s particular difficulties. If your foes are notably tough, the action card governing combat will require extra-careful disc placement. If movement is hindered, the travel card will be stuck with low values. Depending on your characters’ priorities, however, you can seek out opportunities to improve those actions. There are story beats aplenty in Thorgal, but some of the most worthwhile, especially in a scenario’s early stages, are those that let you swap out one of the cards on your action line for something more potent. Suddenly previously-fraught combat becomes a little easier, or your new movement card lets you bring a companion along whenever you dart between regions, or you can scoop up extra pebbles and branches.

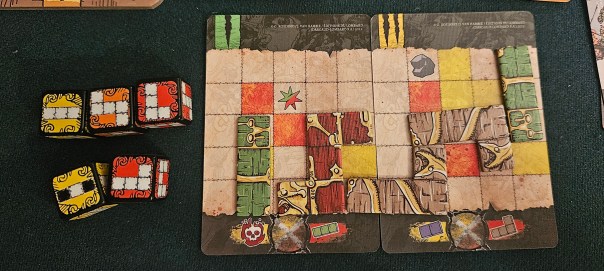

Thorgal’s other unifying mechanism is polyomino placement, a concept that feels abstract for all of ten minutes before it settles into the backdrop.

These shapes stand in for a few different things. Your characters’ health, for example. When you take wounds, rather than simply picking up injury tokens, the way most board games have done in the past, here you assign a shape to your personal grid. If ever you can’t assign a shape, well, that’s curtains for your Vikings. It’s a frankly brilliant system, evocative in a way that blood-red tokens have never managed, providing a striking visual for your character’s waning endurance and turning health into a little minigame that suits the game’s emphasis on survival. Cramming your injuries together to maximize leftover space feels like packing a wound, while fitting a sprawling shape onto your character board comes across as coping with a grievous injury.

That same wound system applies to your enemies, although here the goal is to cover all of a rival’s heart icons in order to wipe them out. Along the way, you can also cover experience points or resource icons to claim their benefits, but must avoid covering shaded spaces lest you incur injuries of your own. This transforms combat into something almost elegant, each shape presenting a slash or crushing blow, a dodge, a parry, a killing stroke.

Somewhat more remote is the journey system. This functions almost like a background in parallax, a reflection of your characters’ wanderings across the landscape that isn’t literally reflected in their on-map movement. Here too you place polyominoes, covering resource-gathering icons and avoiding injuries or other threats. This is Thorgal at its most disconnected, but it still gets across the idea that your band is covering vast distances and overcoming myriad obstacles.

These systems come together to produce an adventure game that not only feels totally unlike anything else out there, but also varies in its experience from chapter to chapter. When fleeing from a furious caliph’s goons, the journey cards become a tale about dodging through alleyways and scuffling with palace guards. When battling multiple cards laid side by side, those grids recall an enemy horde. In its abstraction, Thorgal manages some surprising evocations.

Of course, none of this would matter without some solid scenario design, and this is where Thorgal shines most brightly. Its tales are told in snippets of text, but these are always carefully connected to the game’s systems, offering decisions that have actual gameplay ramifications. Choosing to light a structure on fire to draw away enemy raiders sees those enemies displaced on the map. Gaining allies or seeking a vantage point may permanently alter the effectiveness of your action cards.

There are other, smaller touches as well, resource tokens and all that. But the game’s most skillful touches are those that physically alter the game space. A stolen boat, with its fresh grid for absorbing damage. An overlay that reduces the cost of a destination on the map. A pregnant woman secreted among face-down item cards, nearly discovered at random whenever you cross a checkpoint.

Simiński and Vignaux don’t merely invent new systems; they incorporate them fully into the ludic texture of both their gameplay and narrative. Along the way, they also manage to make me care about these people. I may not know the first thing about Franco-Belgian comics, but I’ve now spent enough time in the company of Thorgal, Jolan, Aaricia, and Kriss to want to see them safely on their way. I’m greedy enough that my main complaint is that I’ve finished all seven chapters and wish there were more to explore.

In other words, what an unexpected treat. May we see more collaborations of this stripe from Kijanka, Święcicki, and Szyma.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on December 4, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Portal Games, Thorgal. Bookmark the permalink. 12 Comments.

Come on, don’t you know Tintin, the smurfs, Asterix ? ^^

Thanks for the review. I’m really wondering how much this polyomino system holds up, it seems so disconnected from the narrative of the game. Glad to hear at least that the scenario design is good.

Honestly, I’ve read like ten comic books in my entire life, so while I’ve heard of those comics I actually haven’t read any of them.

Great review, you have my interest piqued.

You bastard.

PD: “Yet Kijanka, Święcicki, and Szymaimbue each scenario” I think there is a typo here. I spend 5 minutes before realizing “Szymaimbue” was not the last name of the designer 🙂

Aaaaa these Polish names really throw me for a loop.

Thanks for the correction!

There is a second typo of this sort in the last sentence 🙂

Dammit! Thanks for the help. 😉

About 30 years ago when I studied at the university, I lived in a shared apartment with a guy who was collecting comics.

So, I was able to read and learn to appreciate quite a few excellent series, e.g. ‘The Incal’, ‘The Quest for the Time Bird’, ‘The Dark Knight Returns’ ‘Watchmen’ (which is the only series I decided to buy for myself a few years later), and also ‘Thorgal’.

When I saw the announcement for the kickstarter campaign it didn’t take me long to decide I wanted to back it. I was a little worried because there was little to no buzz about it (at least on BGG), so I’m quite happy it left a good impression with you!

The kickstarter version comes with three additional scenarios, btw!

I’ve read Watchmen! It’s very good! I think I once read The Dark Knight Returns… other than that, I’ve read DIE, Maus, Mind MGMT, Locke & Key, The Wicked + The Divine (but not all of it), Uber, Harrow County, and Manifest Destiny… and that might be all. Also, it would be pretty easy to figure out which ones I read as research for board game adaptations.

To be clear, I’m not opposed to comics! It’s just that a fella can only have so many hobbies in one lifetime.

Now I wish I had the KS version of Thorgal. I really hope they add additional scenarios in an expansion or sequel.

Here’s another reader shocked that you didn’t know about Franco-Belgian comics, the third great school/tradition along Japan and the US. I was an avid reader when I was a student (using the local library) but just as boardgames, comics are an expensive hobby, and with boardgames the chance that you’ll consume each item more often is higher.

I think you’d greatly enjoy all the works of (my favorite comic artist) Jacques Tardi. His WWI novels, his crime book adaptations and his weird historical urban fantasies. If you need a board game research as an excuse, start with “Verdun 1916 – Steel Inferno” which uses his art on the cards. (Or maybe have a look at the oop Terrain Vague.)

I could also see you enjoying the works of Lewis Trondheim and his most popular character Lapinot (in English apparently “The Spiffy Adventures of McConey”), an anthropomorphic hare that has lots of doubts and experiences adventures in different times and places throughout the books. (Board game research: The upcoming Unlock! Risky Advenures)

Ah, Corto Maltese, of course, as the Franco-Belgian school includes Italy. There’s a game of the same name as well. And Snowpiercer was of course also a French comic book originally (“Transperceneige”), and some French people made a semi-coop game about it. Alas, it’s only available in French.

Thanks for the miniature history lesson! For some reason, I had assumed Snowpiercer was Korean — probably because the movie adaptation was directed by Bong Joon-ho. My experience with comics is direly limited, even when it comes to US comics.

How’s the replayability of the scenarios, after you’ve beaten them once?

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Adapted! | SPACE-BIFF!