Girder Up

Tower Up is one of those titles that proves a board game doesn’t need to be complex to conceal untold depths. Designed by Frank Crittin, Grégoire Largey, and Sébastien Pauchon, this another game about real estate developers doing their thing and earning big bucks, with faint but clear brushstrokes from Sid Sackson’s Metropolis or Klaus Zoch’s The Estates. But in spite of its vertical development and intersecting player interests, perhaps its biggest departure from those predecessors is found in its dead simple internal arithmetic.

First, let’s go with the simple.

Turns in Tower Up are so obvious that even I can handle them after a dad-brained day of ferrying kids between activities. There are only two options: choose a card or break ground.

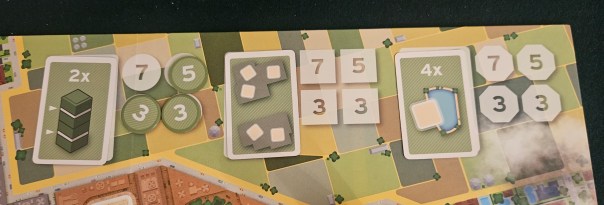

That first option is the breezier of the two. As a developer, you only have so many floors in your possession. There are four types in all, color-coded brownstone, gray concrete, black steel, or elegant white granite. With three cards on offer, you select whichever one suits your current needs. Totally out of black floors? Grab a card with some black floors on it. We’re on autopilot here!

Breaking ground is somewhat trickier thanks to this city’s irascible zoning board. You’re always required to place a floor on ground level, and always next to another building, but your new tower can’t match the color of any adjacent buildings. Also, you’re required to add a matching floor to every one of those neighbors. Socialism it is, I suppose. Finally, you place one of your rooftops on any of the buildings you just built.

Once these rules are internalized, which only takes one or two reminders, the whole thing is a cinch. Bit by bit the city grows from a few starting points, like watching Conway’s Game of Life if those cells ever developed a taste for stacked capitalism.

But this is also where Tower Up starts to develop a headspace of its own. Almost immediately, every placement requires its own set of considerations. Before long, those considerations creep outward to influence — nay, infect — the game’s simpler aspects.

For instance, nabbing those cards. Because you’re always forced to add floors to next-door buildings, it’s worthwhile to hold a healthy stockpile of floors. But this is also a race to place as many of your rooftops as possible, so you’re always running razor-thin margins, keeping your stockpile as empty as possible.

Another example arises from the placement of those actual rooftops. Whenever you place a roof, you score points by moving along the corresponding color of track. Placing a rooftop on your brand new level-one brownstone would only be worth one brown point, while piling it onto the neighboring six-story granite skyscraper would be worth six white points.

Okay, so it’s obviously better to go for the tall structures, right? Well, sure, sometimes. There are other details in play. Such as moving along all the tracks. As you complete certain columns, you earn bonus turns. You read that correctly: entire turns. In a game where the real real estate is temporal, getting to pick an extra card or even break ground twice in a single sitting can be a tremendous boon.

Meanwhile, everybody is chasing bonuses from side objectives. There are three per game, randomly selected, all of them as deceptively simple as everything else in Tower Up. Perhaps you want to be the first to have rooftops on two buildings across neighborhood boundaries, or have ownership of four buildings next to parks, or simply pile a bunch of your buildings into a contiguous chain.

Of course, it’s a rare session that doesn’t feature some sort of blocking. Rooftops indicate your ownership stake in a building, but they can be covered up by additional floors, and therefore be capped by other players’ roofs. This doesn’t deprive you of your stake in that building — indeed, it’s sometimes the case that an objective will explicitly require you to have a covered-up roof. Still, for scoring purposes it’s better to be on top. AND IN THE GAME. Pardon me. My editor informed me that I was contractually obligated to include that line.

But this draws attention to the game’s emphasis on blocking. Consider the following details. One: You can only add a rooftop to a building you actively developed this turn. Two: You can only develop a building if you break ground on an empty lot next to it. Three: This city’s squiggly-line adjacency soon hems in its structures, sometimes with soaring towers that are developed by multiple players, other times with isolated single-floor structures that nobody bothers to renovate further. Four: You can always see which floors your rivals are holding, which means there’s nothing stopping you from starting new buildings that prevent them from adding to the real estate they need to meet their current objective.

Conclusion: Lots o’ jackassery.

As a game about real estate development, it isn’t especially accurate or even all that mathy. There are none of the major turnarounds of The Estates, no auctions to speak of, no crippling debts that might leave your company ruined. In their place is a ground-floor take on the industry that still has sharp enough teeth to leave puncture marks. The rules are simple. Navigating those simple placements in such a way that maximizes your score, hobbles everyone else’s tally, and doesn’t make so many enemies that the entire table dedicates a few turns to caulk-blocking your own renovations — that’s the complicated part.

It also helps that Tower Up is a looker. Once, I lost by two points because a tower was so tall that I couldn’t see an essential empty connection behind it. That’s on me. Even though a session occupies less than an hour, this is still the sort of game that’s worth rotating one’s field of vision by forty-five degrees to get the lay of the land.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on November 4, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Monolith, Tower Up. Bookmark the permalink. 7 Comments.

Caulk-blocking – A’mason pun!

Nice!

I agree! I don’t think this is correct though: “it’s sometimes the case that an objective will explicitly require you to have a covered-up roof”. As I read the goals they all just require the ‘presence’ of a roof.

Yeah, that was vague; the objective that requires two roofs in a single building necessitates a covered-up roof.

ah yes!

I was enamored with Tower Up after the first play, and I ordered it immediately afterwards. I like when tense decisions derive from simple game play. Great game!

Glad to hear you’re enjoying it, Lee!