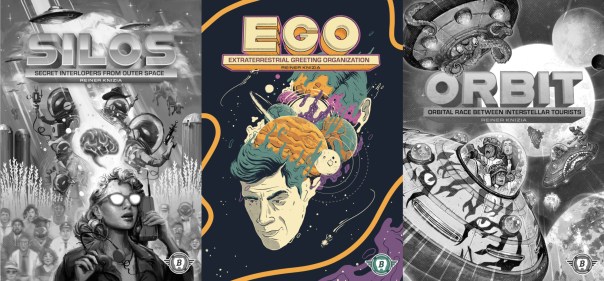

Intergalactic Knizia, Verse Two: Ego

As luck would have it, getting abducted by cow-loving aliens isn’t the worst thing to ever happen to humanity. That’s right, Reiner Knizia’s Silos provides an unexpectedly happy ending. No longer prod-fodder for extraterrestrials, we now stand on the cusp of entering the intergalactic community.

Ego is the second volume in Reiner Knizia’s intergalactic trilogy. With a single vessel prepped for interstellar voyage, diplomats from every nation are ready to explore the farthest reaches of deep space. Their five-year mission: to make friends with strange new peoples; to swap technology to our mutual benefit; to hopefully not embarrass our species too badly. Don’t count on that last one.

Just as Silos was a reworking of Municipium, Ego reaches into the Good Doctor’s back catalog for a title that hasn’t been readily available for over a decade. The target of this makeover is Beowulf: The Legend from 2005, which like Municipium was often derided for a perceived disconnect between its setting and what the players were actually asked to do. Personally, that friction never struck me as particularly noteworthy. As a member of Beowulf’s entourage, one would naturally collaborate with their peers to defeat Grendel and the Dragon while also competing for renown and attention. Like, that’s a sixth-century Scandinavian warrior’s whole deal.

Regardless, Ego smooths over that apparent tension. As humanity’s representatives, you share a spaceship, but everybody is out for themselves. Your goal is more or less the same as in Beowulf. You’re along for the ride, hoping to put humanity’s best foot forward, but you’re also determined to present your faction as the most capable of the bunch. We may have joined the intergalactic community, but that doesn’t mean getting along with our next-door neighbors is any easier.

What follows is a linear journey that begins in the Solar System, crosses three randomly-selected sectors, and then loops back home, with myriad pit stops along the way to gather resources, make trades, and negotiate with alien polities. While the visual design starts out somewhat cluttered thanks to its vibrancy, it doesn’t take long for the iconography to come together. Even the linearity is a boon, letting players examine the remainder of the flight to determine which resources to spend and which to hang onto.

That’s the critical part, because resources are everything in Ego. Your main currency appears in the form of cards with icons; this is your walking-around money, and you’ll spend a great deal of time accumulating, swapping, and spending these cards on everything from tense diplomatic standoffs to blind auctions. But these are only the most fungible of your resources. There are also credits for buying goods, alliances that can be kept for points or traded for other bonuses, and “offense,” portrayed as angry alien babies. These last tokens are a measure of how much you’ve ticked off your various hosts, and canny players will keep their new allies as un-peeved as possible.

It isn’t always possible to stay on an alien’s good side, however. There are little systems aplenty in Ego, but the most interesting of them deals with risk-taking and its possible consequences. Fans of Beowulf: The Legend will recall that the risk-taking mechanism of that game was a source of some contention. In Ego, the entire thing has been revamped and given greater depth thanks to a wider range of possible outcomes.

It works like this. At various moments, you’ll be presented with the opportunity to take such a risk. Maybe it will be during a straightforward exchange of cards, or perhaps you’ll be able to pause a negotiation to gather a few extra crucial icons and swing an alien dignitary to your way of thinking. Whatever the reason, a risk lets you draw a certain number of cards from the deck. Your objective varies depending on the risk, but their commonality is that you’re searching for a particular set of icons. In the usual Knizia fashion, these portray specific in-game objects such as gifts or technology, but in practice they’re orange boxes, halitosis sparkles, moai heads, and Illuminati eyes, alongside pink flowers as wilds.

Depending on your draw, one of three things happens. If you draw nothing but the icons you were searching for — a true rarity, but not impossible — then your risk has paid off. You add those cards to your hand or their icons to your negotiation, depending on the context. Good job! Bask in the glow of everybody admiration/hatred.

On the other end of the spectrum, a total failure is a minor relief. By drawing no matches at all, your diplomat has humiliated themself so thoroughly that the aliens are perplexed rather than offended by your behavior. You don’t gain any cards, but neither are there any penalties other than your immediate retreat from the current negotiation.

A mixed success is where things fall apart. You pick up whatever cards match the desired icon(s), but you also gain some number of those angry baby tokens. You’ve successfully pressured the locals, but in the process also given them some reason to hold a grudge against your faction. Enjoy your nasty alien babies. Hopefully you can find some way to offload them before you reach Earth, because they’re worth a heap of negative points.

In other words, the entire risk-taking system rewards either total success or total failure — or at least doesn’t penalize failure too badly — while loading the long-term consequences onto the more common outcomes in the middle. It’s a smart remediation of the original system, blunting the binary win-or-lose states that were so contentious in Beowulf without totally removing the need to consider each risk.

Good thing, too, because this is the meat of Ego. Sessions only include a few negotiations, scattered among the many other events your voyage happens upon, but contests to flatter those alien dignitaries are tense, confrontational affairs. Wise players will hoard icons for these watersheds, and even then it’s usually best to see how much you can get for as little as possible.

I mentioned yesterday that Silos demonstrates Knizia’s aptitude for centering player psychology. The same is true here. Often the difference between second and third place in a negotiation will be fairly minor. You don’t want to come in last, lest you get saddled with one of those angry babies, but achieving first place might cost too many icons. The entire game swiftly becomes one of assessment, both of a particular encounter’s rewards and its associated risks. Smart delegates know when to fold.

Along the way, Ego tweaks the Beowulf formula in other ways. In addition to the revamped risk system, there are now also reasons to keep cards on-hand rather than splurging everything on the final negotiation. When your ship finally returns to Earth, there’s one last chance to exchange your leftover resources for a large infusion of points. This adds a cutting edge to each spent card. Should you force your way to the top of this particular negotiation or hold onto those icons for the points they’ll confer? Such questions rarely have clear answers.

It helps, too, that each leg of the journey presents its own distinct demands and opportunities. Unlike the tale in Beowulf, which always followed the same beats in sequence, here your voyage is marked by the different sectors your ship passes through. There are four in all but only three appear in each game, and this variability requires players to approach each session afresh rather than copy-pasting the same priorities from the last session. Journeying through the alliance system is a chance to pick up a bunch of special tokens for hidden rewards, while the treasure system sees players wagering credits at every opportunity. The sinister system is the most distinct, packed with alien babies awaiting adoption. Safe passage through that red zone is an exercise in minimizing damage rather than maximizing reward.

The remarkable thing about Ego is the way it feels like an alien journey without the burden of chrome or even any text descriptions at all. In some instances, such as when one is left to decipher an extraterrestrial hieroglyph that’s only slightly different from one of its cousins, that strangeness is perhaps too credible. The rest of the time, Ego’s voyage is sharp and exciting, with everybody jostling shoulders on the ark but still determined to forward their own interests.

In the contest between it and Silos, I prefer the previous entry, although only by a hair. To my surprise, though, playing through the entire trilogy in a single night saw opinions starkly between the two, with some advocating for Ego over Silos or the other way around. That’s another of Knizia’s fingerprints: his fans have a way of turning his best titles into a deathmatch competition for priority. What a comforting capstone to yet another remake of an overlooked title.

Tomorrow, Orbit.

Ego, along with Silos and Orbit, is on Kickstarter right now.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A prototype copy was provided.

Posted on October 16, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Bitewing Games, Board Games, Ego, Reiner Knizia. Bookmark the permalink. 19 Comments.

A minor point but Beowulf let you trade unspent cards for points at the end too.

Thanks! Yeah, I learned Beowulf yesterday, but it was… a rather flawed teach.

You might be misremembering, but Beowulf ends with the “Death of Beowulf” episode which is basically a simultaneous auction with all of the cards left in players’ hands. Then players select a reward on the wheel in winning order (5 points or discard a wound, then 4 points, 3, 2, 1). There is no trading/exchanging of unspent cards for points at the end, so Dan’s description was correct.

Since there are no decisions about which cards to play in that episode, it feels like trading everything in for points rather than an auction. I realise that it is not exactly the same as what happens in Ego 🙂

Now I don’t know who to believe!

(Glad my play of Beowulf wasn’t totally broken!)

We’re all right!

Haha, I’ll take it!

The thing I like about EGO’s ending is that you are torn between going hard on the final auction and saving those cards for the final option events (trade 3 symbols for 5 points, etc.). It’s a tough call that all depends on how hard your opponents are going to bid in the auction.

With Beowulf, the final auction is climactic (play all your cards!) but predictable (the player with the biggest hand is gonna win it).

It was cool to see Knizia make subtle but impactful improvements like that outside of our specific requests.

Did you get a chance to try any of the expansion material?

I did, and unlike Silos, where those materials aren’t necessary, here they offer some real improvements, lengthening the duration of your overall journey. I would recommend using them for Ego.

Well, EGO has two different types of expansions. The expansion boards are in every copy and lengthen the game by adding new events to the first four planets. That includes the new credit and transmission events. The ships and special alliance tokens, on the other hand, will be sold separately but are included with kickstarter.

Personally, I wasn’t planning on getting more than one game but can’t decide if EGO interests me more as a game or if I’m just in love with the art. We’ll see.

Yeah, it’s a hard one. I would say Silos, but enough members of my group preferred Ego that I’m not comfortable calling it.

Thanks for another great and thoughtful review! On hearing Silos was a reworked Municipium I was in. Beowulf is less appealing, but the tweaks seem like they only improve the system.

Thanks for reading! I’m definitely of the mind that Silos is great but Ego is still very good.

You don’t even want to know what that “caster ring” is in my, uh, circles…

Ew! (Nice.)

Love the shout out to Gene Wolfe. Just finished rereading Fifth Head of Cerberus.

A master of fiction.

Pingback: Intergalactic Knizia, Verse Three: Orbit | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Intergalactic Knizia, Verse One: Silos | SPACE-BIFF!