So It Goes

Before he became a famous author, over a decade before Slaughterhouse-Five, Kurt Vonnegut was a board game designer. A failed board game designer, with only a sheaf of notes, a single rejection note, and an unfinished patent to his name, but a board game designer nonetheless.

And now his sole surviving design is an actual board game you can buy and play and, if you’re anything like me, spend a few hours marveling at. Thanks to the efforts of the Vonnegut estate in preserving his notes and Geoff Engelstein in interpreting and tweaking them into a functional state, GHQ — short for “General Headquarters” — is, not unlike Billy Pilgrim, a thing unstuck in time, transported from 1956 to 2024.

In his pitch letter to Henry Saalfield of the Saalfield Game Company, Vonnegut talked up his design, as one does when trying to interest a publisher into taking more than a cursory glance at something you’ve spent the past year testing on the neighborhood kids. “It has enough dignity and interest, I think, to become the third popular checkerboard game,” he wrote. “The game would, I’m quite sure, satisfy the faculty of West Point as a tactical demonstrator.”

I’m not sure about that part, but GHQ does have a certain depth of place to it. The shorthand is that GHQ is to WWII what chess is to the Medieval battlefield. Where chess speaks to feudal realities — expendable serfs, riders who exploit openings rather than dash themselves against spears, the weirdly militarized influence of the church — GHQ proposes its own axioms.

Your goal is to destroy the enemy’s headquarters, thus decapitating their command structure and presumably ending the conflict, although in practice sessions tend to conclude in surrender a good dozen turns before that happens. The principal delineation is between infantry and artillery. There are different forms of each archetype — mechanized infantry move faster, heavy artillery lob their shells farther — but everything on the field can be sorted into one of those two categories.

These unit types operate according to distinct rules. Infantry are flexible, moving and capturing opposing pieces first by engaging with them, their little arrows — which Vonnegut’s early notes evocatively call their “business end,” calling to mind the barrel of a rifle — pointing toward one another to indicate their engaged status, and then, with the assistance of a second infantry unit, flanking and destroying the piece. One can practically hear the “Find-Fix-Flank-Finish” of 20th-century infantry drills being boxed into one’s ears. Artillery, on the other hand, is lumbering but destructive. These pieces rotate their barrels along fixed axes, creating zones of destruction that, if not swiftly vacated, will demolish every opposing piece along the line of their plunging fire. Unsurprisingly, artillery is achingly vulnerable along every avenue they aren’t currently aiming at, providing little inroads for canny infantry divisions to exploit.

It’s funny, the way we look at chess and forget that these knights and bishops and pawns and doddering royalty were once the thematic side of the hobby. It takes something like GHQ to snap that historical distance into focus.

Here’s an example. The most potent of Vonnegut’s pieces is the airborne infantry, capable of dropping onto any open space on the board, but only if they begin their move on your back row. As soon as they’re deployed onto the board, the airborne make themselves an ongoing threat simply by sitting there. Unless you’re looking to allow some crucial artillery pieces to be captured, you soon screen your flanks and rear, carefully positioning infantry around your cannons so that enemy airborne can’t take them out on a whim. It only takes the smallest opening for a bold commander to shatter the composition of an entire front with the right drop. But then, as soon as they’re on the ground, airborne make a target of themselves. They’re as flimsy as regular infantry, and often worth a sacrificed unit or two to capture. So the game turns briefly into a clash of kill and rescue missions, one side racing their mechanized units forward in an effort to clip their rival’s wings, the other slipping their boys back across the lines where they can be outfitted and dropped once more.

As vignettes go, that’s a shocking degree of evocation for a game that predates Risk or Diplomacy. It’s also only the first of a few small touches that feel commonplace now but were downright innovative in 1956. As Engelstein’s commentary points out, GHQ may well contain the world’s first instance of zone-of-control rules. Once engaged, infantry are stuck in place; they can withdraw to a non-engaged space, but cannot, for instance, sidle through fire to engage and destroy another unit. The board, too, feels dynamic in a way that slots into the tradition of abstract wargames. About midway into a session, when a tangle of units has been arrayed and overlapping fields of fire emanate from various artillery pieces, it isn’t hard to imagine some mid-century grognard investing in a plotting rod to nudge his pieces across the grid.

It’s also so very Vonnegut. Years before Billy Pilgrim manifested as his coping mechanism for the horrors he witnessed in the Ardennes and during the firebombing of Dresden, here he was designing a game that drew on his experience as a spotter for the 106th Infantry Division. It’s a game rooted in a particular military doctrine, one where most casualties were not inflicted by tanks or planes, but by distant cannons. While the game’s airborne units are flashy and threatening, it’s the roving fields of fire that shape this battlefield.

That, too, strikes me as the proper way to consider GHQ. Vonnegut’s antiwar stance crystallized as U.S. involvement deepened in Vietnam, and it’s natural to wonder if the older Vonnegut set aside GHQ not only out of disappointment with Saalfield’s lack of interest but also because its maneuvers and bombardments cut too close to the bone. The author had been shelled by the Germans in the Ardennes, strafed by the R.A.F. on Christmas Eve in the boxcar that carried him to Stalag IV-B, and then, while performing hard labor for his captors, as he wrote it, “On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F. Their combined labors killed 250,000 people in 24 hours and destroyed all of Dresden — possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.”

Maybe I’m reading too much into it. My grandfather was a bomber squadron commander in that same war’s Pacific Theater, and while he hated the pointlessness and absurdity of war, he never shed that portion of himself that appreciated the skills he had developed, the knowledge of aviation and bombers and which segments of a bridge were most vulnerable to demolition. But he also screamed in his sleep and suffered flashbacks in which his plane was going down again and exited the exam room for a deep breath whenever a Japanese patient came into his office. He was both men.

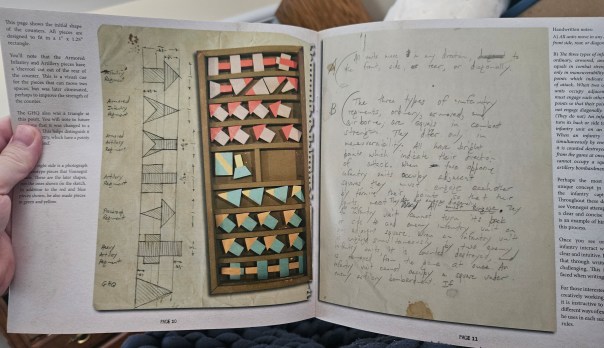

In that regard, GHQ is worthwhile for the same reason that any beloved author’s lesser-read books are worthwhile, because they offer a few more hours in the company of this person who has brought wisdom and thoughtfulness and beauty into our lives. Engelstein reproduces Vonnegut’s notes, typed and handwritten alike, providing a window into his version of what we would call the development process. We see the designer grappling with how to explain infantry engagements, the way his later efforts double in length and provide gameplay examples, the gradual clarifications to his terminology. It’s technical in a way that his novels are not, but that doesn’t make it any less his.

If anything, there are familiar touches: the billowing smoke clouds of an artillery impact, redolent of his illustrative style; little asides scratched out and replaced with more concise expressions; precise pencil slashes where the author has decided to try his phrasing again. Perhaps most of all, it’s the density of it all, the lived-in-ness, the semi-autobiographical touches. Thanks to the game’s authorship, when an infantry piece is shelled and removed from the game, this is no mere abstraction, or not only abstraction. It is the 106th Infantry Division being blown to pieces and having over 6,000 men captured in the span of a few days. It is those same men traveling via unmarked rail cars that drew strafing fire. It is those men working themselves ragged in a malt syrup factory and getting caught in an Allied atrocity. It is the same absurdity and pointlessness that would cause Billy Pilgrim to become unstuck in time and find himself among creatures who witnessed the death of the universe but could do nothing to stop it.

Is GHQ a good game? Sure. For its time. For its place. Had it appeared in 1956, it may well have become the third great checkerboard game. With its zones of control and special units, it might have helped shape the coming century’s approach to tabletop gaming.

But that isn’t what happened. In our time and place, GHQ is a serviceable game. It suffers from the same endgame as many modern abstracts, packed with fiddly little moves that amount to very little. We would write that it could have used a good developer. But that doesn’t really matter. Instead, we get the second-best outcome. Because GHQ isn’t only a board game. It’s a piece of history that has come unstuck and traveled from its time to ours. It’s a surprising ludic evocation — of the awe reserved for the airborne, of the terror of crawling fire, of the sheer casualties inflicted in such a war — authored by somebody who went through it. It’s another hour or two with an old friend long passed. So it goes.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on September 25, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, GHQ, Mars International. Bookmark the permalink. 19 Comments.

Interesting that it uses a diceless resolution mechanic. Does Vonnegut discuss why he did it that way, or was it just assumed based on the boardgames he was familiar with (chess and checkers)?

I think it’s because he was trying to create the “third great checkerboard game,” and 1956 is early enough in the history of modern board games that dice resolution for something like this was still uncommon. Risk came a year later, for instance, and Charles Roberts was still popularizing CRTs for wargames — Avalon Hill wasn’t founded until ’58, so it’s entirely possible that Vonnegut wouldn’t have considered dice at all.

I have a deep love for Vonnegut’s books. I found them when I was 17 years old and they resonated deeply with me. I heard about this game and will have to get a copy for that reason alone. Thank you for this review as it does help me refine my expectations a bit!

Happy to do it!

Always important to point out that the number Vonnegut gave for the firebombing of Dresden was wrong by an order of magnitude. He was—unknowingly—regurgitating one of Joseph Goebbles’ most successful late-war propaganda coups: modern scholarship places the death toll in Dresden at somewhere between 22000 and 25000 people. The Reichsminister and his propaganda ministry added an extra zero to the figures, shifting a decimal point and in doing so transforming with the stroke of a pen a shocking loss of life into one of the most grotesque losses of life of the war.

But it was a political lie.

Correct. Thanks for the note.

Beautiful timing. I only just watched the “Unstuck in Time” documentary about Kurt a couple of months ago (which I absolutely recommend), and then bought the complete collection of his short stories right afterward, which I’m still pouring through. That this review came out now feels like a natural extension of this being a theme in my life for the last few months. Long live the ‘gut!

How very serendipitous!

Enjoyed the review. It does a nice job of explaining the context of the game’s development and its mechanics.

But I don’t agree with the conclusion.

I haven’t found it is packed with fiddly moves. It is quite chess-like and with equally skillful players, it becomes a game of attempting to suffocate your opponent with overwhelming attack vectors. Almost like a constrictor slowly suffocating its victim. Small moves are made to apply that pressure. They are only fiddly or meaningless if you plan poorly or, perhaps, don’t know what you are doing.

And the endgame is similar to chess in that it typically ends in a surrender (as you noted) rather than outright capture of the enemy HQ. That’s not a problem. The meat of the game is in gaining an insurmountable upper hand over your enemy. When both agree you’ve achieved that, there’s no point in going further.

It’s a good game today, not merely serviceable. I think it is appropriate to see it as being similar to chess although substantially different enough to be its own, unique, experience.

I think it’s a feat of amazement in itself this game is getting to see the light of day.

Given that Kurt Vonnegut would have only had access to a very limited selection games in the times in which he was living, for the game to be as positively playable as it is, with no internet to draw inspirations from other people’s creations, no discussion boards, likely limited access to many seasoned play testers and the market was just tiny in those days, in general, just less interest and feedback from other human beings. I think for something that someone put so much time and effort into to finally be published and be experienced by people is inspiring to the act of creation itself. For it to be reinforced that even if one is not published or known in their creative endeavors, (be it board games, or writing, music, drawing or any form artistic expression.) have people experience their work is very hopeful indeed.

While chess/and checkers may have been the primary inspiration for his game design, we create by what we know. Given those games’ historic longevity, (and I still find chess to be “fun”, I suppose) even being mentioned alongside them is a high form of praise. So, what if it doesn’t make the cut compared to such historic classics as Pandemic, Carcassonne, or even the almighty patchwork and may not sit next to the PBR in the holiday gift basket to my friends? I now get to play the only game ever created by one of my favorite authors, and one of the most prolific authors of the 20th century. And that is worth more to me than it being the third most popular checkerboard game of all time. (He was obviously trying to sell himself, create interest and just have a bit of fun)

Great points, John!

Also, forgot to say. Thanks for the review! I enjoyed it

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 9/26/24 What A Knitted Sweater Would Look Like If I Scrolled One And Pixel Two | File 770

Pingback: Stick to baseball, 9/28/24.

Pingback: September 29th – Critical Distance

Pingback: 《往事如烟:GHQ,库尔特·冯内古特的二战桌游》 - 偏执的码农

Pingback: New Itch Games From August and September – Indie RPG Newsletter

Pingback: Space-Cast! #43. Unstuck in Time | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: SDHist 2025: Day of Copium | SPACE-BIFF!