Arabian Hammer

Periodization is a funny thing. Sorting history into discrete blocks is useful for the sake of memory and study, but often proves misleading the instant somebody takes those blocks as gospel rather than as a loose mental framework.

Take the unification of the Arabian Peninsula. From the European perspective, the ascent of the House of Saud was paved by the evaporation of the Ottoman Empire. On the Peninsula itself, however, the conflict had deeper roots, bound up in feuding tribal dynasties, the distant interests of multiple imperial overlords, and the passage of many decades.

Arabian Struggle, co-designed by Nick Porter and Tim Uren, and drawing on the Conflict of Wills system initially expressed in Robin David’s fascinating Judean Hammer, emphasizes the long view. A dozen wars, countless battles and raids and negotiations, and even the Great War itself are mere beats in its epochal narrative. At ten thousand feet, the details get fuzzy. It’s to Porter and Uren’s credit that the overall thrust of the conflict never goes missing.

There are three principal actors, identical in terms of raw ability, but quickly distinguished by geography, various events, and outside forces.

The most recognizable is the House of Saud, the historical victors of the unification. Occupying the arid plateau at the peninsula’s center, the Saudis seem like the natural whipping boys of the conflict. To their south is the Rub’ al Khali, the Empty Quarter, a vast desert that provides a natural boundary for the conflict. To their west, the House of Hashim occupies the coast, including control over the holy cities Mecca and Medina. To their north, the House of Rashid commands the mountainous Ha’il. The Saudis might as well be a soft-shelled crab caught in a lobster’s pincers.

But external interests prevent any one faction from gaining too much ground. When the game opens, the Ottomans occupy much of the coast and the northeastern region of Iraq. As time progresses, the Great War sees the British enter the peninsula. Eventually, as the Ottomans are defeated abroad, their withdrawal opens new areas to tribal expansion.

Of course, it’s possible to go to war with these imperial adventurers whenever you like. But that’s a testy prospect thanks to the combat system Robin David pioneered in Judean Hammer.

Battles are straightforward affairs in Arabian Struggle, but that doesn’t mean their outcome is certain. Your initial strength is derived from two sources: your chits on the map and any modifiers thanks to ongoing events. It’s rare for these numbers to get much higher than, say, four. Maybe five if you’re rocking some good benefits.

You march into a contested area. Battle between tribal forces is the natural state of things; the instant the Saudis, Rashidis, or Hashemites coexist in an area, combat is destined to take place at the end of the turn. Squatting on imperial land is a different story. To them, you’re a footnote. At best, you’re occupying the land on their behalf as a vassal. At worst, you’re a pest in the corner, as easily squashed as ignored. To initiate combat with an empire requires a precious action point — a high price to pay when you could be marching against your true rivals or bolstering the defense of a crucial city.

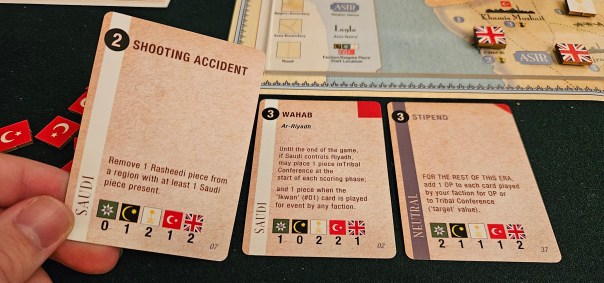

In both cases, battles are resolved by drawing a single card from the top of the event deck. Each card shows five combat modifiers, one per faction. You gain the bonus for your faction, while the target of your attack receives theirs. Total value wins. Both sides roll for casualties, with the loser taking one guaranteed loss and potentially having their entire force broken apart.

Here’s the rub. Modifiers only go so high. Most of the time, your highest possible modifier is two. Three if you’re the Saudis. Empires, though? Their modifiers often go all the way up to four strength. Those imperial chits may seem isolated, but there’s a reason they claim control of a territory even when you outnumber them. Their potential combat values are hard to match without significant preparation.

As is the norm in historical games of this stripe, cards are useful in multiple senses. Usually, you’re given the choice between spending a card for its action points — to bolster and move your forces — or to trigger its printed event. There are some limitations here. Events are powerful, but many of them are tied to specific eras. To give just a few examples, the Saudis can only deploy Ikhwan missionaries after they’ve leaned into Wahhabism, the Iraq Rebellion isn’t going to happen until the British control Iraq, and the Hashemite alliance against the Ottomans can only occur during the Great War. There’s nothing quite like the relief of seeing your hand packed with opposing events only to realize that none of them can trigger in the current era.

As event systems go, this is old reliable, but it allows Porter and Uren to import another trick from Judean Hammer. When events are triggered, they’re permanently tossed out of the game. But this also means that their battle modifiers will never again appear from the deck. Naturally, your best modifiers appear on the cards coded to your faction. Now you’re presented with a choice. When one of your events is offered, should you trigger it for an immediate benefit? Or slide it back into the deck to hopefully win an important battle in some future era?

The effect of these deck alterations is subtle. Certainly it’s more muted than in Judean Hammer, where slotting modifiers into the deck was often necessary if you hoped to succeed in the game’s second half. But while these manipulations aren’t as preeminent as they were in that title, they can still be the difference between seizing a rival capital or watching as your army is utterly destroyed by a casualty roll or cut off from crucial supplies.

This is the one arena where Judean Hammer was clearer in intent. In nearly every other respect, Arabian Struggle produces the more dynamic experience.

Let’s talk victory. Points in Arabian Struggle come from three sources, with each avenue demanding its own considerations. First is battle. Winning an attack might award a point. Might. In order to win a “great” victory, and therefore earn a victory point, you need to fully rout your opposition. That means emptying the space you invaded of opposing pieces. This naturally lends itself to easy victories, swooping two or three chits into a territory with only a single enemy chit, lest your rival survive their casualty roll and force your troops to retreat. In turn, this encourages a different sort of thinking about warfare. Big clashes produce big swings, and are often essential for seizing major territory, but they’re also dangerous. Minor battles prove your tribe’s prowess and earn points. It’s a fitting contrast for a conflict where the Saudi conquest of Riyadh consisted of fewer than a hundred fighters per side.

The second source of victory points comes from the tribal conference. This is a minor occupation, producing only a point per turn at most, but given how often Arabian Struggle comes down to one or two points, it shouldn’t be neglected. Sending representatives to the conference is uncertain: you toss out a card to roll against its combined action value and battle modifier. But this is also an opportunity to ditch a card entirely, usually one that would prove too beneficial to a rival. It’s the same basic function as the Space Race from Twilight Struggle, letting you trim your hand of opposing events. At the same time, spending too much effort on the tribal conference can deplete your manpower, especially once you have three or four representatives who could instead be out seizing and holding territory.

Finally, each era concludes with every faction assessing their relative control over the game’s nine regions. This is easier said than done. To control a region and earn a point, you must command the majority of that region’s population. Empires control their territories, even if you somehow outnumber them, often producing infuriating ties that leave you swearing vengeance against the British.

Making matters even tougher, not all of a region’s population is stable. In addition to urban populations, the map is speckled with nomads. These count as population for whomever controls them, and can be pushed around at periodic intervals. The problem is that nomads are just as likely to raid their occupiers as you are. This prompts a roll that might remove one of your chits — and let me tell you, it’s holler-worthy when your control over a contested region disappears thanks to the key nomad wiping out your forces.

Put together, these victory conditions generate their own vicious ecosystem. The Arabian Peninsula feels alive and dangerous in a way that very few card-driven wargames have managed. While those three belligerent tribes vie for territory, the game of empires thunders overhead and nomads scurry underfoot. This is a world of divisions and spheres, but riddled with portals that might admit a daring emir — or a bullet.

This tenuousness is also essential to the game’s unique character. Arabian Struggle is playable with only two people. In that mode, the Saudis and Hashemites war for control of the peninsula while the Rashidis function as a card market of potential events. It works, and it’s still good, but the two-player mode also sheds the anxieties of the regular game. At three, nothing is certain. While the Saudis begin in a vulnerable position, they’re also free of the burdens of empire. It isn’t long before the other factions find their own pressure points. Will the Hashemites and Rashidis come to blows over Transjordan? Will the temptation of Iraq and Kuwait draw some heat? What will happen along those tender borders between Madinah and Najd, or down in Asir, or along the plains of Ar-Riyadh?

I have yet to play Arabian Struggle without witnessing a shift that felt like the turning of an era. In one session, the Hashemites lost their home and starved along the frontier when the supply phase came around. In another, the Rashidis unified the northern portion of the peninsula and left the Saudis languishing in the desert. More often than not, the Empty Quarter has turned into a key supply route for a Saudi bid on Yemen. Watch those flanks. The Hashemites are right there.

I’m sure there are points that some would consider negative. It’s dicey. The events are sometimes straitjacketed to their respective eras. The deck-arranging thing isn’t as colorful as in Judean Hammer.

But those are minor detriments, if that. When a game occupies little more than an hour, as Arabian Struggle does, I can forgive bad rolls and poor draws. That’s doubly true when a game is this vibrant, this fully realized, this packed with clever touches that evoke a wider world. In Arabian Struggle, Porter and Uren present one watershed after another, a series of imperial blunders, tribal raids, and nomadic migrations. This is the making of good history, a top-to-bottom investigation of how this slice of the modern world was forged along disparate vertices. Conflict of Wills, indeed.

Arabian Struggle can be preodered over at Catastrophe Games.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on August 15, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Arabian Struggle, Board Games, Catastrophe Games. Bookmark the permalink. 8 Comments.

Really glad to hear this game worked for you. I’m excited to try out Judean Hammer, but the topic of Arabian Struggle is much more my jam.

Funny, it’s the opposite for me! But this is the better game. It builds on the original system in really cool ways.

Thanks for the review, this game looks very interesting. I love games that cover obscure (for the West) topics like this.

Me too!

Apologies for the oddity of this, but this review gives me such vibes of an old globe I recently found in a storage closet at work. I -think- I’ve dated its creation to somewhere between 1922-1930, based on what’s there, though I’m no historian and mistakes will happen.

Transjordan, Persia, and French West Africa (among others!) were all red flags. I get warm fuzzies when I recognize something like Transjordan in my day. I work for astronomers, not historians, and the timescales there get -super-weird sometimes…

I love dating maps by their now-outdated boundaries! What a fun find.

This one seems sweet. I always think of myself as someone who abhors wargames. And yet, I also find myself attracted to the ones you talk about.

Perhaps it is a question of scope.

Could be. It might also be that I don’t write about the really knotty wargame stuff. I’m generally not interested in hex-and-counters or anything a think tank might use to train military officers.