Friends Don’t Let Friends Slay Alone

Cards on the table: I prefer Monster Train.

But it would be folly to deny that MegaCrit’s Slay the Spire has wielded massive influence over the digital deck-building sphere. Without Slay the Spire, an entire cohort of excellent successors would never have strode forward to claim the throne. Still, despite the odds, Slay the Spire remains unbeaten, a modern classic that’s less a game and more akin to a digital addiction.

How Gary Dworetsky got the go-ahead to adapt it for tabletop is beyond me. Don’t get me wrong, Dworetsky is a talented designer, and his previous game, Imperium: The Contention, as unfortunately titled as it may be, was fantastic. But it was also his only previous game. There’s probably some insider baseball we’re not privy to.

Not that it matters. Whatever its provenance, Slay the Spire: The Board Game is here. And it’s good. Every bit as good as the video game. Which isn’t the same as saying it’s an essential title.

For the uninitiated, Slay the Spire wears its intentions on its sleeve. You adopt the role of a hero (antihero?) scaling the titular spire, mass-murdering monsters and barely scraping past hulking bosses. Your goal? To slay the spire, silly.

There are four character classes in all, nicely differentiated from the usual fantasy fare but still recognizable enough. There’s the Ironclad, equipped with a big sword and a beefy healing factor, who’s really good at smacking monsters with said sword. The Silent is the game’s rogue analogue, doling out poison that gradually eats away at a foe’s health and tossing shivs in those moments when you desperately need to deal just a teensy bit of extra damage. My personal favorite class, the Defect, is a robotic summoner that surrounds itself with hovering orbs for passive damage and other effects. And then there’s the Watcher. She’s like a ninja, with multiple stances that she shifts between. I don’t really get the Watcher, maybe because she was the last character released into the video game, and by that point I’d moved on to other things.

Right away, Slay the Spire sets itself apart in a few ways. Part of its lasting influence is the way enemies operate. Each round, they declare their intentions up front. This guy is going to weaken your attacks. His buddy plans to stack your deck with fire cards, which will injure you over time. And the last guy intends to smack you with some regular old damage. Now you react. Maybe you focus your damage on a single enemy to prevent him from triggering his ability. But which one? Sometimes it’s wiser to guard yourself from an attack, or use an ability that will prepare you for the next round. Often, there will be surprising or unorthodox solutions. How you respond is up to you.

Up to you and the deck you’ve prepped, anyway. That’s the other thing about Slay the Spire. Each character has their own pool of cards, a selection that randomly presents itself over the course of a run. Nearly every battle concludes with you opening a booster, drawing three cards off the top of your upgrade pool and choosing which one to add to your deck, or passing entirely if everything on offer would merely gum up the engine you’re putting together.

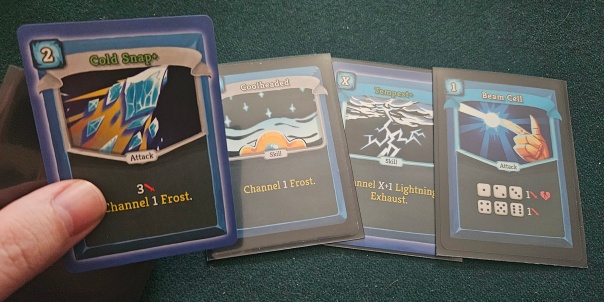

One advantage of Dworetsky’s physical implementation is the ability to actually see these stacks of cards. There’s an obvious tactility to having these things arrayed on the table rather than listed on a screen. If you’re anything like me, this also makes the decks easier to handle, to sort through, to choose what to upgrade. Your table becomes your user interface, infinitely adjustable to your current needs. Like the cards in Skye Larsen’s Paperback Adventures — which owes its own pedigree to the original incarnation of Slay the Spire — all your cards are necessarily sleeved, permitting dual faces that can be upgraded to more potent forms. This fills each session with all the pleasure of crafting the perfect deck for Magic: The Gathering, or whatever your childhood money-sink happened to be.

And it’s a very real pleasure, a throwback to adolescence as much as it is an adult exercise in numerical optimization. I say you’re crafting the “perfect deck,” but what I really mean is that you’re crafting the perfect imperfect deck. You’re working with whatever the boosters have provided, your pocket change — or in Slay the Spire’s case, your dwindling health— transmuted into commons, uncommons, and rares. When Brad Talton designed Millennium Blades, he sought to replicate the dopamine hit of opening a booster pack before you’d even left the comic shop, swapping cards with friends, fretting over the arrangement of your collection in a binder, agonizing over whether to part with a beloved card on the aftermarket so you could afford something that would better suit your tourney deck. He understood why these rectangles of cardstock matter to people.

Dworetsky also understands why they matter to people. More than that, he understands how to adapt a complex system so that it doesn’t require a computer to crunch numbers in the background. As a digital game, Slay the Spire hides much of its work beneath the hood. Not only the big stuff, like calculating massive hits, but also the subtle randomization of encounters and card draws, enemy behavior and when a relic will trigger its ability.

In most spots, Dworetsky lassos the heights of the digital version and drags them back to earth, decreasing the original game’s integers by one or two orders of magnitude. This results in a range that’s comprehensible to mere mortals. The Ironclad begins with 10 hit points rather than 80. Your starting attack cards deal 1 damage rather than 6. A boss monster may well still have a hundred hit points (or three hundred), but they’ve been streamlined in other ways.

Contrary to what one might think from the outside, retouching these numerals is no simple matter, especially now that every hit matters. Losing three hit points represents a third of your character’s entire health pool. The distinction between three damage and four might represent a significant leap, especially when dealing damage to an entire row of monsters. Even if the tabletop version of Slay the Spire had only been rebalanced, Dworetsky would have managed quite the feat.

But that isn’t the only adaptation to consider. There’s also the dice system. Or rather, die, singular, since you only ever roll one of the things. At the start of each round, you roll the die. This determines… well, a lot of stuff. Principally, it determines the intended behavior of the monsters you’re facing. Whether they’ll hit you with honest damage or launch a more crabwise attack. Some enemies, bosses in particular, rotate through a set of behaviors; for the most part, though, it’s the roll that picks what they’ll do at the end of your turn.

This already does a lot of heavy lifting, offloading potentially overwhelming randomization to a single digit. Dworetsky doesn’t stop there. As a character, you’re also gathering relics that trigger special abilities to help in combat. Many of these only activate on particular rolls, transforming that opening roll into a determiner not only of enemy behavior, but also of your own potential. And that’s before we consider certain cards. Rather than letting cards produce randomized results, as could occasionally happen in the digital game, Dworetsky instead ties the application of certain cards to the die roll. This allows some cards to produce multiple effects, while offering slight balancing touches to others. To use another Ironclad example, the card Spot Weakness can strengthen any character, making their attacks more powerful, but only if that round’s roll was 1-3. Rather than being an obvious inclusion in any deck, Spot Weakness is now a considerable but uncertain option, something that may require chance or outright manipulation of the roll to reach its greatest potential.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s still a lot of upkeep. As you climb the spire, everything the digital version would have automated falls to you, the player, to manage. The semi-randomized tiles that mark the various paths upward must be seeded at the beginning of each act. Events have their own deck. Everybody has multiple card pools to manage. Encounters must be populated from stacks of regular, elite, and summoned enemies. In some cases, an elite or boss will summon a few mooks from an earlier act’s deck; these are always clearly indicated on the cards, but reaching back into the box for a dismissed stack can feel like a bridge too far. There’s bookkeeping aplenty.

So much bookkeeping, in fact, that on more than one occasion the process has benefited from a support staff playing Houston to our Apollo mission. In our last session, we had four people playing the actual game while two friends sat on the sidelines, making suggestions and keeping enemy status tokens straight — and that was only a portion of their duties. They also shuffled and distributed potions and relics, populated encounters, hunted through decks for misplaced cards, set aside anything we culled from our decks, and doled out and discarded curses and affliction cards. The session moved noticeably faster, with fewer pauses to prepare another combat encounter or fill the shop with relics and potions. Slay the Spire isn’t unmanageable without helpers, but it’s telling that it benefits from them.

I’ve buried the lede, because the real highlight here is the ability to play with friends. Climbing the spire with more than one class is exactly what I wanted from this adaptation. I’ll even admit that it’s why I prefer Monster Train, with its focus on combining two factions per run. I love those combos. Let me build a team, not just a character.

In that regard, Dworetsky’s adaptation of Slay the Spire doesn’t disappoint. Putting two, three, or (YES) four characters side by side is a treat. And it’s such a natural inclusion. Each hero faces their own lane, filled with monsters that mean them harm. But each hero has broad latitude in where to direct their attacks. A natural camaraderie arises. Certain enemies, especially those that threaten a killing blow or will strike every hero at once, become the target of focused assaults. Bad hands are mitigated by teammates rushing in to bop one of your monsters or temporarily raise your guard. Dworetsky even provides a reason to tend to your starting Defend cards. Rather than being fodder for deletion at your earliest convenience, they can now be upgraded to guard any of your friends. It’s a subtle but clever touch, adding depth to even early builds.

Not every decision is divided equally. Your fellowship is still bound together on the map, for instance, so there’s some room for disagreement if one person wants to hit the shop while someone else wants to tackle an extra elite. But these are minor beats in the game’s overall story arc, so minor that they quickly fade into the backdrop.

On the whole, Slay the Spire rises or falls based on its multiplayer. Because while certain weirdos — me — might be more inclined to play at the table than let a computer handle all the heavy lifting, the adaptation is so tight that there isn’t much to see apart from the higher player count. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying there’s nothing to see. Dworetsky has done yeoman’s work at not only transposing the gameplay, but improving upon it in minor ways. The increased emphasis on decks over relics, alongside the more parsable numerical density, means that a successful build isn’t quite as reliant on stumbling over the proper relics. This is still a roguelike. Failure lurks around every corner. But it feels a little more yielding than its digital originator.

Also, one can cheat. You know, if cheating was something one wanted to do. Perhaps to mitigate an utterly stupid roll or draw, or to reorder a misplaced order, or to rewind to the start of an encounter to see if things might have played out a little bit differently. The ability to not only behold a system in its entirety, but also manipulate that system at will, has always been a significant advantage of solitaire tabletop games over their more, ahem, enforced digital counterparts.

Either way, the fact stands. The biggest draw here is the ability to put multiple heroes next to one another. This cannot be overstated. The challenge of facing multiple lanes of foes but being free to combine abilities — it’s a scream. And it feels wholly perfect, the Ironclad marking an elite as vulnerable so that the Watcher can launch a wrath-fueled attack for double damage, only to trickle them to death with some poison and lightning from the Silent and Defect. It’s such a natural way to play that it’s easy to forget this wasn’t the default mode all along.

So we return to the opening question. Is Slay the Spire: The Board Game an essential title? Not for solo players. Despite some minor improvements, it’s hard to imagine opting into a four- or five-hour session over a full-auto digital run. On the other hand, as a multiplayer experience, there isn’t anything quite like this adaptation. With friends, it’s not only a faithful adaptation; it’s a genuine reimagining of what makes Slay the Spire so wonderful. I seriously doubt I’ll ever play it alone again. Slay the Spire: Together.

And Gary Dworetsky! If you’re reading this, see about the rights to Monster Train. CHOOT CHOOT.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on June 11, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Alone Time, Board Games, Contention Games, Slay the Spire. Bookmark the permalink. 10 Comments.

I’ve had this hit the table 4 times already and have been fairly disappointed with it.

Yes, he managed to capture the balance of the existing game into one that works as a board game. That was very impressive!

And yes, the co-op is the new feature and key to enjoyment of it!

But the design of these two points ended up opposing each other and I think this is where he really made a misstep.

When players can direct attacks where they will, many defenses where they will, which lanes they stand in after seeing the monsters… and the core experience falls apart. In a laughing-full-of-comradery way, but it still falls apart.

That enemy that gets stronger every time you hit it? Just don’t hit it until your team is ready to focus-fire it. That enemy that gets stronger every round, focus-fire on round 1 or 2. A player without enough defense? Focus fire that row. A player with strong attack cards they can’t play because they need to play defense? Focus that row, so now they can play their attack cards to relieve the next player, etc. You aren’t so much as four Slay the Spire players helping each other out as much as one large unwieldy organism that draws 20 cards and has 12 action points.

Every combat ends in ~2 rounds (bosses in 3), so powers or other cards that need time to pay off really don’t.

We tried just skipping a ton of ascension levels. We tried played with a couple of total newbies who spent more time flirting than playing and just carried them. Still ended up having the encounters go roughly: “I bid 12 damage”, “I bid 21”, “I can safely do 6 but if I don’t have to block can do 18 and apply a vuln”, “My biggest hit is 10, let me use your vuln and I’ll unpin you”, “Okay round 1 done, fully blocked, two rows left to clear, let’s count to 38 and then clean up.”

He captured the balance in easy-to-parse-numbers and then threw it all out of the window. We never even used the “swap rows with another player” cards. We kept assuming we misread the rules over and over again because attack anywhere is far too powerful. Why not “clear your row and THEN attack anywhere”? Or why not have most cards be something like “attack your row OR the one on the left”? Why are we even drawing monsters for EVERY row, why not just make normal fights like the boss fights, where the monster is designed around focus fire and is beefy enough to actually get to do what it is designed to do. Then boss fights should have been something bigger. Less drawing tons of baddies, less paperwork, fights that ensure they have time to employ their gimmick and time for you to maybe play a couple of powers.

Sorry. I liked your thoughts. I guess I had lots of thoughts too!

You can’t switch the row AFTER monsters spawned. Switching is only allowed between combat rooms (see End of Combat.)

Besides it, satisfaction of the coop board game depends on the style of play group. If you prioritize the optimization and coordinate everyone’s hands, it’s your choice.

I have played with only 2 players. But then I felt the fact that player can save another one leaving the enemy in front of them is some dedication. It recollects me the implementation of Marvel Champions.

Thanks for another awesome review, Dan!

I think that’s not representing the game well. It might be easier on Ascension 0 than the video game, but it’s harder on Ascension 12 than the videogame is on Ascension 20.

The balance is there, it’s just that they made the base version easier to avoid roguelike frustration in a 6 hour board game, which I think is a very fair design choice.

While powers might trigger less, I also found them to be way more impactful even in the short run.

Getting 1 strength a turn in this version is more like getting 5 strength a turn in the video game.

Dan I have a secret for youthat might revitalize your life ve for digital slay the spire (all people who do not like cheating close your eyes and ears): You can cheat in Slay the Spire like in the boardgame, if you go back to the main menue during an encounter or a card choice/relic choice it will reset, beacause it lonly saves in the beginning of the encounter. I use it to play by feel instead of crunching numbers and sometimes to puzzle out if an encounter was winnable after all.

Good to know! I should note, I’m not desperate to cheat. It’s just that in a board game, I can lose the game, then play through to see what might have happened.

You should check out Across the Obelisk, it sounds like the digital counterpart of this implementation. I’ve had a lot of fun playing through it with my brothers.

Interesting! Thanks for the recommendation!

Pingback: Ode to the Depot | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Best Week 2024! Adapted! | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Boss Cells | SPACE-BIFF!