Smuggin’

Word games. Specifically, that subset of word games that we call conversation games. They’re tougher to create than they might appear from the outside. And I can’t think of a better example than Phil Gross’s ContraBanter, a title that’s loaded up with great ideas yet still doesn’t quite work as intended.

Imagine two teams of competing smugglers. (ContraBanter permits up to three teams, but let’s keep this simple.) In front of each team sits a selection of three words. These words are ordinary enough that they might appear in a regular conversation, but not so often that their appearance won’t be notable. Redo. Eagle. Omen. Shark. Fever. Lighter. That sort of thing.

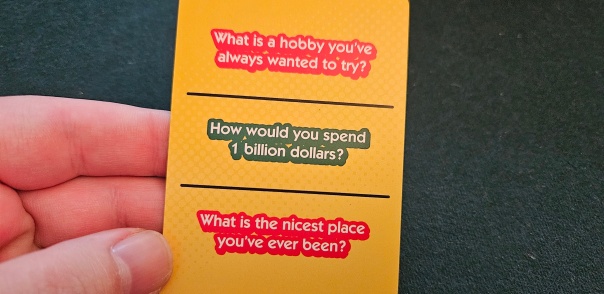

Somebody starts a timer. The listening team asks a question. In the event that you can’t think of anything, ContraBanter helpfully provides prompts. “Share a thought that keeps you up at night.” “If you could be any animal for a day, what would you be and why?” That sort of thing.

Then it begins. The listening team listens while the smuggling team smuggles their words, via conversation, past the listeners. Basically, you chit-chat. Kvetch. Shoot the breeze. Confabulate. Jaw. Gab. Natter. Chew the fat. That sort of thing.

Somewhere along the way, the listeners can pause the timer to guess a word. They get three guesses within the span of that 90 seconds. If they guess correctly, they steal the word from the smugglers. If not, well, then they don’t. Then the timer continues. So does the conversation.

Optionally — although I do recommend this — there are “marked cards,” specific words that the smugglers are encouraged to not say. If uttered, the listeners can claim the marked card. Like smuggled words, these are worth a point apiece. They also tend to be more common fare. When. How. Because. Now. In. Cool. Why. That sort of thing.

When the ninety seconds is up, the smugglers earn a point for every one of the hidden they slipped past the listeners’ net. Except they keep those words. Because in the next round, they’ll continue smuggling the same ones. Which means that certain phrases will send up flares when they’re repeated.

Now switch sides. Both teams get three chances to listen, three chances to smuggle. One point per intercepted word, one point per smuggled word, one point per marked word. That’s the game.

As conversation games go, ContraBanter’s greatest success is that it’s surprisingly low-stress. Unlike, say, Spyfall, where everybody at the table will be thrust into the spotlight whether they’re good at these sorts of games or not, ContraBanter allows the shy among us, the quiet, the introverts, the bashful, diffident, sheepish, timorous wallflowers, to contribute only as much as they feel confident.

And that shouldn’t be overlooked. Because even mousy or timid players can enjoy a game about prevaricating. It’s just that some folks don’t want to be the absolute center of everybody’s scrutiny. By putting everybody on a team, ContraBanter allows everybody to participate on their own terms. That’s an admirable accomplishment.

At the same time, there is so much room to game this game. Not just room. An entire countryside.

Let’s say one of your words is “cougar.” How are you going to work that one in? Let alone work it in multiple times over three rounds? If you’re a member of a gang of ailurophiles, perhaps there will be a natural entry point. Maybe you’re a fan of Mormon sporting events. Or a connoisseur of the ABC/TBS television series Cougar Town. Or perhaps you’re aware of some other, potentially sexual connotation of the word.

Or you could bring up cats and list as many breeds as possible. “My bad dream is that I work in a pet store with Joe Exotic,” you might say. “We had tabbies. Lynxes. Ocelots. Lions. Leopards. Cheetahs. Servals. Caracals. Cougars. Mountain lions—”

“Fossas!” somebody offers.

“Fossas aren’t cats,” somebody else says. “But you know what is a cat? Bobcats. Sand cats. Bald cats. Egyptian cats. Siamese cats.”

(You have just done something clever. One of your other words was “bald.”)

And here’s the problem: ContraBanter isn’t really about saying words. It’s about synonyms and static. It’s about flooding the airwaves with so much noise that your opposition knows the gist of your word but doesn’t have a reasonable probability of guessing the correct one. Because surely, at this point, they’re aware that one of your words is cat-related. But which of those dozen-plus words should they pick?

Does this go against the spirit of the game? Maybe. Probably. But only the spirit of the game, not the letter. The rules ask that players abstain from speaking gibberish, belting out random words, or speaking glossolalia. But what constitutes “random”? There’s no guiderail here, no way to prevent a team from skirting the border of what’s acceptable. To once again invoke Spyfall, that game smartly constrained people’s potential guesses to a visible set of options. By letting an entire language’s lexicon function as the game’s guess list, the listening team is overloaded with possibility.

That’s only one example of how fast-talking players are able to railroad the action. As long as one’s patter hits enough beats and peppers the conversation with enough not-quite-innocuous filler terms, it’s trivial to smuggle those assigned words. Bonus points if you remember your fillers and work them into the next round’s conversation. Either one team gloms onto a workable strategy and dominates the whole thing, or else both teams figure it out and the discourse becomes an incomprehensible mishmash, like listening to old radio comedians pelt their audience with six hundred words per minute.

Of course, there’s another option. Maybe neither side takes it all that seriously. That’s the best outcome. If nobody puts any muscle into trying to win this thing, then ContraBanter remains a perfectly pleasant conversation game.

But that’s no outcome at all. As a non-universal guideline, it’s a poor game that requires everybody to play it poorly. Perhaps that’s what ContraBanter, which is a light party game after all, is going for. Except it only takes one person to interject that unwanted confrontation. One person who worms themselves into the gaps of what’s permitted. One person who isn’t actually breaking any rules. That’s the problem. ContraBanter may be friendlier to introverts, but it doesn’t understand why genre-defining titles like Spyfall, Insider/Werewords, and Blood on the Clocktower provide ways for players to narrow their guesses. Those reductions are necessary. They cut through the noise, bring the static into focus, revolve the color wheel until it resembles the outlines of a picture. Without that, all that remains is a jumble.

Despite the simplicity of its rules, ContraBanter is in the jumble business. It’s a game that only functions as intended when everybody declines to use a few readily apparent strategies. For all its cleverness, it doesn’t unscramble the static. There are better light party games aplenty.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on May 30, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, ContraBanter, Skybound Tabletop. Bookmark the permalink. 4 Comments.

This quickly reminded me of the deduction with light roleplaying game Inhuman Conditions.

essentially it is a board game version of the voight kampff test where one player is a human trying to deduce if the other player is a human or android.

If you are an android you have certain conversation rules you must or must not do. Yet there are tons of options for limiting your conversational style where this just seems to be do/don’t say X.

I’m a big fan of IH but as it is typically a 2p game it seems like there is a lot more stress than this larger group game.

Now I want to try Inhuman Conditions!

“Kvetch” means to complain, not chat. Perhaps you were thinking of the also-borrowed-from-Yiddish “schmooze?”

Nah, I meant complain. Like you can all sit around and complain to each other. Maybe it wasn’t a natural usage, I dunno.