More Like Hadrian’s Pathetic Ditch

It isn’t that I dislike the entire roll-and-write/flip-and-write genre. It’s that the genre never grew past its infancy. There are exceptions. To give one example, I recently enjoyed Steven Aramini’s Fliptown enough to name it one of my favorite titles of 2023. For the most part, though, these games feel more like proofs of concept than something I’d elect to drag off the shelf.

That is, until I played Bobby Hill’s Hadrian’s Wall, a tangle of possessives if ever there was one. I’ll do one better: This is Dan Thurot’s Bobby Hill’s Hadrian’s Wall review.

You probably know the backstory. In the early second century, the Roman Emperor Hadrian built a wall across Britannia. Raised the whole seventy miles with his own two hands, he did, felling trees with his palms and cutting turf with his teeth. Or he sent a bunch of soldiers and slaves to do it.

Bobby Hill leans into the latter interpretation. A wise choice, since the first one hasn’t appeared in any history books. As history-making, Hill does something a little bit wonderful. Our understanding of the wall is spotty, but it was clearly a massive undertaking, requiring six years and likely tens of thousands of laborers, not to mention the enormous force of soldiers and auxiliaries that eventually staffed it. Hadrian’s imperial project, in marked contrast with his predecessor Trajan, was about securing frontiers rather than expanding them, and the wall that bears his name seems to have been crucial to the development of Britannia as a thriving province.

Hill gets that. As a representation, then, this is a military project, but only in part. It’s also an act of nation-building. Hadrian’s Wall is about piling stones and digging ditches and fending off Picts — soldier stuff — but it’s also about opening markets and putting on displays of Roman power, proving your backwater province has the potential to become cosmopolitan, and fostering a healthy degree of bureaucratic corruption. It’s about the trappings of empire as a multiplicity rather than stopping at the legions who usually constitute the Roman Imperial face of our cultural imagining.

It’s also one heck of a grand flip-and-write game, perhaps in part because while it embraces the genre’s conventions, it isn’t hidebound by them.

Take, for example, the structure of a single round. There are six in all, each standing in for a year of the wall’s construction. When each year opens, you’re allocated workers and resources by Hadrian. In true flip-and-write fashion, everybody receives an endowment of soldiers, builders, slaves, civilians, and resources. Because Emperor Hadrian is very far away indeed, these allocations appear as a lump sum. If you need extra builders but mostly receive settlers, tough. If you’re low on slaves to perform the menial work of gathering wood and stones, tough. If you’re super invested in the local theater but Hadrian sent you a bunch of soldiers instead of clowns and performers, tough.

On the far side of each round comes the invasion. Much like the round-opening allocation of resources, everybody at the table now faces a barrage of flipped cards representing the various flanks of the Pict invasion. Hand it to the Picts, they sure are organized, assaulting each section of the wall in identical ranks.

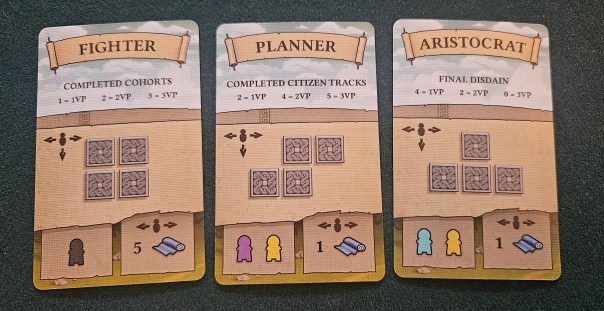

Except in both instances Hill allows for flexibility. While everyone at the table receives an identical ration, you have some wiggle room. You can foster an income of builders, civilians, and extra stones on your sheet, setting your legion apart from your neighbors. Meanwhile, every round also begins with each player drawing a pair of cards and choosing how to use them. One will become an end-game scoring bonus. The other does a few things, but its immediate perk is an extra couple of workers.

As for the invasion at the conclusion of the round, you have all the necessary tools to avoid any fallout. First, of course, you could raise sentries, ditches, and walls to stop the Picts outright. This is the most obvious solution, but it’s also static and liable to fall apart if you don’t secure the proper flanks. Other options grant more leeway, like sending out diplomats to ease relations with the local tribes or praying to the gods for some limited intervention. If those fail, a bunch of sweaty bureaucrats — literally sweaty, since they do business in your newly-heated bathhouse — can paper over any disgrace from a Pict raid.

In other words, Hadrian’s Wall isn’t hamstrung by identical inputs between players. That’s always been a big part of the genre, and here it survives intact. But from that very first opening minute, you’re making individual decisions and taking individual risks. Every approach has its own advantages. Scouting the surrounding terrain yields resources and slaves, but occupies soldiers you might prefer to put on guard duty. Praying to the gods is uncommonly efficacious, erasing a few attacks altogether, but requires a bunch of workers to spend the day prostrate instead of laying stones. Trade is a sure route to proving you’re a big boy proconsul, but wastes your hard-earned resources, or worse provides them to your rivals. The tradeoffs are as legion as the, um, legion.

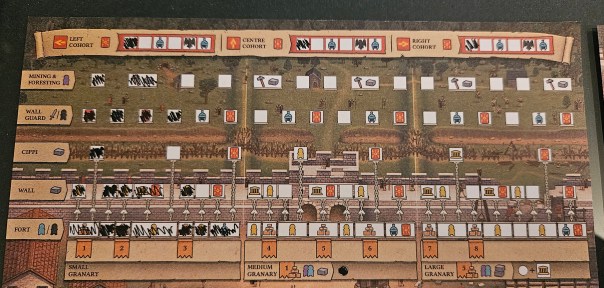

That bigness is another way it sets itself apart. While it’s an exceptionally tracky game, with some tracks nestled inside of other tracks, it only rarely feels like it’s about the tracks. Perhaps another way of putting it is that everything feels coherent within the setting. There are four scoring tracks, for instance, but they represent crucial intangibles that would interest a Roman commander trying to secure the frontier. Improving your garrison’s valor rewards points when the game concludes, but also doles out additional soldiers. The same goes for renown and citizens, piety and slaves, and discipline and workers. These aren’t merely ways to tally your score; they’re worthwhile pursuits in the moment, extending how much you can accomplish in any given year.

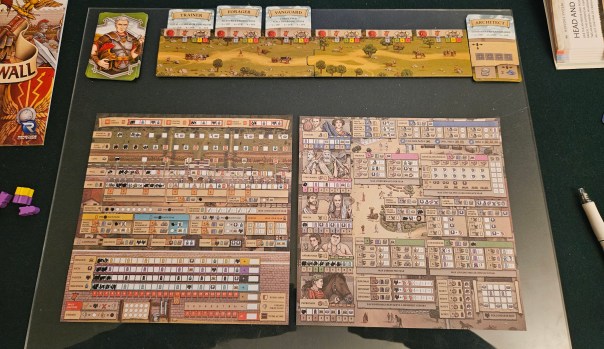

It needs to be said, too, that unlike a number of other flip-and-writes, Hadrian’s Wall doesn’t accidentally become a memory game. In too many of these things, one soon finds themselves buried beneath bonus actions and resources and whatever else. Hill solves the problem by simply acknowledging that there should be actual resource tokens, little laborers of various colors and resource blocks, and then trusting the players to make exchanges as often as necessary. You’re never forced to count on your fingers or make little hatch-marks in the margins just to remember how many extra perennials you can plant. The numbing nested actions of Three Sisters are nowhere to be found.

Seeing these aspects in combination is where Hadrian’s Hall really thrives, though. Where most flip-and-writes tend to produce mathematical puzzles and little else, Hill has his cake and eats it too. There’s a beautiful sense of place to the game. What begins as a few small earthworks soon becomes a sprawling project. Those initial settlers become a bustling populace.

And I’m not only talking about a sensation here. The game really does open up as it moves from year to year. While the first year or two is mostly confined to the left sheet, where one focuses on the practical matters of frontier security and ensuring you have enough material to continue construction, the focus gradually moves to the right side of the play area where your citizens are located. These cover five classes — traders in their marketplaces, performers who can draw wider attention with their antics, priests and their priestcrafts, apparitores with some necessary corruption and class-based antics, and patricians who scout the territory and hopefully ease foreign ire. Some of these even open up the game to broader horizons. Trading and scouting force players to interact with their neighbors, briefly glancing up from the tracks and boxes to swap resources for trade goods or soldiers for segments of terrain, while gladiatorial matches see you dipping into the main deck to see whether your champion got stabbed in the throat this turn. As your sheet becomes more cosmopolitan and far-ranging, so too do your actions as a player.

The result is a ever-expanding game space, one that thrills at the prospect of completing another fortification or levying excess builders to patrol the perimeter, without forgetting to approach its topic mindfully. It’s aware that the Roman Empire was brutal and terrifying to people both within and without its borders. As with all things Roman, there’s a veneer of legality that hides a gnarlier reality. One can, for instance, erect a courthouse in order to enslave locals or manumit slaves into freedmen. In game terms, these realities are couched; Hill uses the euphemism “servant” to stand in for slave, a common practice for English-speakers when talking about the ancient world. But these realities are presented faithfully and acknowledged as viable strategies even as they’re codified as exchanges of a blue meeple for two purple meeples.

Is it a coincidence that the most interesting flip-and-write game I’ve played mechanically also happens to be the most interesting as an explication of history?

I don’t think so. Bobby Hill has created something truly compelling in Hadrian’s Wall. The title sells the game short. It’s about Hadrian’s Wall, sure, but it’s also about Hadrian’s auxiliaries and Hadrian’s engineering and Hadrian’s takeover of neighbors through both hard and soft power, not to mention Hadrian’s laws governing the taking and manumitting of slaves and Hadrian’s imperial stories about himself and Hadrian’s suspicion that gladiators aren’t worth the investment. When I play, my final scores exhibit that it’s mostly about Hadrian’s understaffed ditches. So it goes. Whether I’m erecting walls or digging ditches, this is what I want to see more of from the flip-and-write genre.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

Posted on February 12, 2024, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Garphill Games, Hadrian's Wall. Bookmark the permalink. 11 Comments.

I’m so happy you’re happy with Hadrian’s Wall. It’s a top five boardgame for me. When you get the chance, pour yourself a cup of tea/hot chocolate /bourbon one night and set up a solo play session. It is board game bliss and very meditative. Great write up. Do you also want to eat the Flintstone vitamins that are the games meeples? Is it just me?

*Don’t mix tea, hot chocolate, and bourbon.

Haha, I don’t want to eat the meeples as much as the treasure pieces from the new Libertalia, but I can see the appeal.

I am engaged in Andy Schwarz’s Dan Thurot’s Bobby Hill’s Hadrian’s Wall review reading.

Andy Schwarz

Partner

O|S|K|R

aschwarz@oskr.comaschwarz@oskr.com

W: 510-899-7190

C: 510-333-6591

F: 510-263-6058

I am Dan Thurot’s…

Fine, you win.

Hey Dan,

Thanks for the kind words. I can’t tell you how happy I am that you recognized the history through the ‘box ticking’. I worked hard on getting that right. It means a lot.

Cheers

Bobby

Bobby, thank you for reading — but far more importantly, thank you for designing such a fantastic game!

I couldn’t agree more with your review, this game is excellent with many different strategies to pursue and it’s surprisingly thematic.

I would just add that the campaign mode (available for free on BGG) is an excellent addition. It offers different challenges and emphasizes different strategies. You might ignore Gladiators normally, but a campaign mission might force you down that route and try out new aspects of the game.

You aren’t the first person to mention it! Guess I need to take a look.

Pingback: The Gone Samaritan | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Smurf-Hopping | SPACE-BIFF!

Pingback: Christ and His Saints Were Asleep | SPACE-BIFF!